Robert Lamb (centre back) at tree protest in Lewes. September 2004

What follows is a fuller version of the obituary I wrote for The Guardian which was published on 14th October. Robert was the first person I met, back in 1981, who was talking about deforestation of the tropical forests. He became a dear friend and is sadly missed by us all.

Robert Lamb, who has died suddenly of a heart attack aged 56, dedicated his working life to trying to alert the world to the destruction of the world'sforests, to strengthening the links between environment and development issues and to forging a connection between creativity and the environment.

He was led to a study of the forests through his work as a government scientific officer, which partly involved liasing with the Termite Research Unit at the British Museum (Natural History) in the mid-1970s. This study of wood-eating insects required him to read the forestry literature where he discovered that a lot of alarming things were going on. He searched in vain for a book that provided an overview of the situation and eventually decided to write his own.

'World Without Trees' (1979) pulled together a vast amount of information -the biology of trees, their importance in society, the timber trade,deforestation, tree diseases and the problems of Amazonia. Robert went on to work with World Forest Action from its inception in 1979 to 1982, to try and turn this information into practical action. Set up by the writer and documentary filmmaker Herbie Girardet, WFA was the first NGO to deal with all aspects of deforestation. Both men became part of an important informal international network of writers, researchers, filmmakers and activists who drew attention to this important global issue and sought to make it relevant to ordinary people's lives.

Increasingly, Robert was drawn towards finding ever more creative means of getting the messages across to the mainstream by linking art and environment.

His memorable documentary, 'Mpingo:The Tree That Makes Music' (1992), which he both conceived and appeared in as an expert witness, was directed by Michael Gunton and broadcast on May 3rd as part of the BBC’s One World Week. It showed how many western woodwind orchestral instruments (the clarinet in particular) are made from the wood of the African blackwood tree (Mpingo), a species that was and still is under threat. As a result, a number of classical concerts were held to raise money for more plantings and the African Blackwood Conservation project was founded in the US to raise further funding.

In the 1990s, he began working with Bill Beech at the school of arts andcommunication, University of Brighton, and it was there that he establishedand administered a Life Arts Research Centre; Life Arts was his term forcreative work with an environmental consciousness, another pioneeringeffort. The Centre worked alongside Friends of the Earth to coordinate twoanti-motorway art spectacles - the 'Grey Man of Ditchling' (July 1994)a chalk figure caricature of John Major, created by Steve Bell and land artist Simon English, protesting the proposed expansion of the A27, and the unique Art Bypass event at Newbury (August 1996),comprising the work of 70 artists including Christo, Werner Herzog and Heathcote Williams. His popular biography, 'Promising the Earth', formed an important part of FOE's 25th anniversary (1996).

Great confusion was caused over the years by the fact that there were two Robert Lambs, the other being the founder of the Television Trust for the Environment. First introduced in the mid-1980s by Catherine Caufield, later author of ‘In the Rainforest’, who felt they should meet, they discovered they both had sisters called Susan. To distinguish them, friends used a shorthand – do you mean fat Lamb or Thin Lamb? When the other Robert left his job at IUCN in Switzerland, Robert took it over. The same thing happened at UNEP in Nairobi – which completely confused everybody. After Nigel Hawkes memorably confused the two of them, attributing each of their films to the other in his review in The Times, they mischievously wrote a letter of complaint, entitled ‘Breaking the Silence of the Lambs,’ claiming that neither was the other.

From 1997 to 2000 Robert, now based in Lewes, managed id21, a freeweb-based service that communicates the latest UK-based internationaldevelopment research to decision-makers and practitioners worldwide, part of the activities of the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex - and set his style on it. Robert also made a significant contribution to UNEP’s state of the world environment report GEO 3 (2002).

He spent some considerable time in recent years working on the yet to be published 'A Hungry Ghost', a biography of the Russian-born Dr Barbara Moore, who became a national celebrity in the early 1960s with a series of epic, record-breaking walks from Lands End to John O'Groats and across America, with only nuts, honey, raw fruit andvegetable juice for nourishment.

He was a substantial and warm presence with a big heart and a gift for friendship. Sometimes difficult but never dull, he was passionate and knowledgeable about food (especially mushrooms), fishing, wine, books and music.

Born in Doynton, Gloucestershire, he was educated at Commonweal grammarschool in Swindon, and at Marlborough College, and gained an exhibition toMerton College, Oxford (1968-71). From 1971 to 1983, he worked as a scientific officer for a now defunct branch of government, assisting research in tropical agronomy, entomology and integrated management.work which led him on assignment to the Gambia, Ghana, Niger, Yemen and Nigeria (where he spent extended tours of duty conducting field trials). He is survived by his artist wife Jo and their two sons Ollie and Fred.

Robert Lamb, writer and conservationist, born February 7 1949; died September 12 2005

UPDATE: On November 1st 2005, The Times published the following obituary for Robert. Unfortunately, half of the piece referred to the works of the other Robert Lamb, who wrote a letter entitled BREAKING SILENCE OF THE LAMBS 2 to The Times as follows.

Sir,In 1992 The Times was generous enough to publish a letter by the late Robert W. Lamb and myself regarding the review of Mr Hawkes of two films shown by the BBC on one night. He assumed we were one and the same. 'Neither of us', we wrote to you, 'was the other.' I am bound to point out that you have repeated the error in the November 1st obituary of Robert. At least it is 50 percent correct this time, which is an improvement. The middle bit of your review is all about my films. The pity of course is that Robert W. had achieved quite enough not to have half his obituary given over to an interloper. He would have been amused, though, and it is a great sadness to me that I write this time alone.

Yours sincerely, Robert Lamb (Editor/Earth Report).

UPDATE 2: A fulsome new tribute to Robert by Tom Flynn can be found on Tom's excellent blog The Institute of Flaneurology.

Robert was a contributor to my magazine Tree News and the last piece he wrote for us was this profile of the great tree-planting pioneer Richard St. Barbe Baker. It gives some idea of the depth of his knowledge and his eloquent writing style.

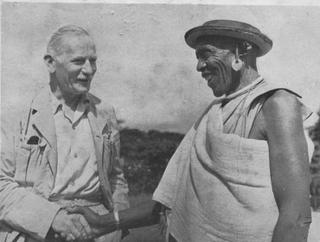

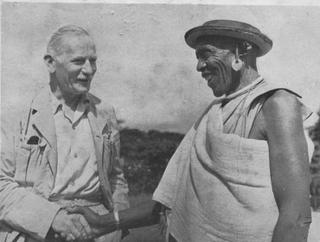

Richard St Barbe Baker being welcomed back to Kikuyu by his old friend Thotho Thongo, who was head moran and leader of the 'Dance of the Trees.'

The Man of the Trees

Robert Lamb

‘In the stillness of the mighty woods, man is made aware of the divine.’

Richard St Barbe Baker

This year [2004] marks the 80th birthday of the Men of the Trees – high time to review the legacy of its charismatic founder, RICHARD ST BARBE BAKER, whose inspired advocacy for trees and conservation made an impact on many lives and landscapes. But has it withstood the test of time?

During his lifetime it is said that Richard St Barbe Baker planted or caused to be planted over 25 thousand million trees. He published some 30 influential books about trees and conservation. In Kenya in 1922 he persuaded a major clan of Kikuyu agriculturists to start up Men of the Trees (Watu Wa Miti). Part secret society, part agroforestry project, part dance ritual, it was the first official effort anywhere to involve local people in what we would now label social or community forestry. A worldwide confederation of Men of the Trees societies grew from these unusual roots.

St Barbe developed a rationale for tree-planting as a universal remedy against desertification and soil loss, and in 1924 he founded the Men of the Trees in Britain to encourage tree planting in this country. He also helped start the Soil Association and the Forestry Association of Great Britain. His forthright views were pretty nearly all there was in the way of modern pro-environment thinking on trees in wide circulation before the early 1960s.

Most who knew him called him simply St Barbe and their memories of his deeds and character tend to embellish both with an almost saintly aura. When he died in 1982, Teddy Goldsmith’s tribute to him in The Ecologist hailed him as ‘a prophet, in the Old Testament sense of the term; that is to say, a wise man, a teacher and an inspirer’.

Less reverentially, Alan Grainger praised St. Barbe’s ‘unique capacity to pass on his enthusiasm to others. Many foresters all over the world found their vocations as a result of hearing the Man of the Trees speak. I certainly did. But his impact has been much wider than that. Through his global lecture tours, St Barbe made millions of people aware of the importance of trees and forests to our planet.’

There is no denying the passion with which St Barbe preached his message, even if it concealed an innate bashfulness which caused him to dread public speaking engagements. Yet without the benefit of a first-person encounter, how should we judge his merits and legacy today?

Christian ministry

A vegetarian pacifist whose first ambition – interrupted by World War I – was to read divinity at college and become an evangelical Christian minister, St Barbe saw a spiritual or ethical point and message in most of his works. In later life he became devoted to the Baha’i faith, a liberal offshoot of Islam that prides itself on blending a scientific with a spiritual world view.

St Barbe’s quest to seek inspirational synergies between science, nature, society and spirituality, contrasts oddly with his private turmoil – including a blighted first marriage – and with his rival pursuits as a man of action, hands-on inventor, astute businessman and avid self-publicist. It can be argued that his quest to latch forestry to spiritual advance led him to warp the borders of both.

His view that deserts inevitably spread because of pressures of human development is notably contentious and appears to connect with myths surrounding the Biblical Fall. He proposed as a millenarian goal for mankind the total ‘restoration’ of the Sahara to what he believed to be its innocent state – a tropical forest – by creating a Green Front of sustainably managed forestry across middle Africa, then gradually shifting it north.

Born in 1889 into a horse-loving Hampshire family with collapsed aristocratic connections, St Barbe was taught to plant tree seedlings at the age of four by his father, who mixed a not-for-profit living as a Mission Church clergyman with running a successful plant nursery. At 20, St Barbe was posted off to Saskatoon in Canada in response to a call for missionary helpers to work with settlers in isolated homesteads.

A lumberjack in Canada

St Barbe prepared for his overseas mission by acquiring blacksmithing skills and camping out under the stars in Hampshire with the son of a local fruit-grower. They planted trees by day then stripped off for boxing and swimming contests in the evenings. Such tales of muscular Christianity and hyperactivity abound in all St Barbe’s early memoirs.

His exploits in Canada were truly prodigious and so were his learning activities. He was one of the first 100 students to enrol for a foundation course in arts and sciences at the newly-established University of Saskatchewan. He paid his way through college by working as a lumberjack and by breaking wild mustangs and selling them on as carriage ponies. He also wrote a sports column for the local newspaper. And he planted trees. In My Life – My Trees, the best-known of a string of autobiographies he published at intervals throughout his life, St Barbe recalls how:

‘While crossing the prairies of Canada, I recognized for the first time a desert in the making. Wide areas had been ploughed up where for centuries dwarf willows had stabilized the deep, rich, black soil. In those days, anybody could file on to a quarter section of 160 acres for nothing … The first thing they did was to plough as much of it as they could then sow wheat and oats to feed the horses. One could travel miles without seeing a tree. With no sheltering trees the soil began to drift and blow away; up to an inch would be lost in a year.’

During the three and a half years he spent in Canada, St Barbe encouraged local farmers to plant trees around their homesteads and as shelterbelts around farms and fields. On university farmland he raised different tree species in special nurseries and experimented with them to find which gave the best shelter. The state government agreed to provide free seedlings to farmers participating in the scheme, some of them part of Mission Church congregations that St Barbe, still set on a priestly vocation, was working with out in the boondocks.

A change of heart was not far off, however. ‘While working in a camp near Prince Albert,’ he later wrote, ‘swinging the axe as a lumberjack, my heart was torn to see the unnecessary waste of trees, and I decided that one day I would myself qualify for forestry work.’

The First World War

World War I spared him from having to choose between souls and saplings. Burying conscientious objections, he enlisted as a cavalry trooper, then was promoted to become an artillery officer. Twice wounded in action in France, he was reassigned to the notionally less hazardous duty of shuttling cavalry horses to and from the Front. In April 1918 another life-threatening injury clinched his ticket home.

He kept bees and enrolled for a Diploma in Forestry at Cambridge. Armistice came soon after and peacetime left big stockpiles of surplus fuselages and undercarriages lying useless in aircraft factories. St Barbe devised a scheme for recycling them to build motor-drawn caravans to his own original design. Intended mainly as a job-creation scheme for ex-servicemen, the scheme turned out a going concern and a conspicuous moneyspinner.

In effect, St Barbe had invented the caravan in its modern, two-wheeler format, a claim unlikely to endear him nowadays to motorists in a hurry or landscape purists. The versatility and savvy his invention had demonstrated stood St Barbe in good stead when in 1920, forestry diploma in hand, he was recruited by the Colonial Office to serve in Kenya as an Assistant Conservator of Forests.

The African years

Africa made a deep impression on St Barbe and Kenya remained a spiritual home to him for the rest of his life. But he was shocked to have to report that much of the forest land in Northern Kenya in and around the Rift had become denuded of tree cover and eroded, leaving the mainly Kikuyu people, who laid customary claim to the area, on the edge of demographic ruin.

‘Whole tribes were dying out, trapped in a triangle of forest with desert in front of them for 1,000 miles, desert behind for 1,000 miles. The chiefs had forbidden marriage, the women refused to bear children. It was racial suicide on the biggest scale the world had ever seen, directly as a result of forest destruction.’

St Barbe admitted part of the problem was land clearance on a vast scale by Asian contractors preceding white settlers. Yet he decided the main culprit was ‘the nomadic methods of farming which had devastated vast tracts of the African Continent’ and had been brought south by descendants of nine of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, followed by ‘wave after wave of Arabs with their goats’. Native forest dwellers, ‘men who lived by the bow instead of the hoe’ were displaced, leaving the land defenceless.

‘There was but one hope, and that was to restore the indigenous forest. I demarcated a large area and had it gazetted as a forest reserve. Cultivators were used to clear the rubbish and plant young native trees between the corn and yams so as to leave a potential forest behind them. Thousands of transplants were needed. I enlisted the cooperation of the chiefs of the area . . . but the young warriors seemed more interested in dancing than in planting trees. So I said, “Why not a dance for tree-planting – a Dance of the Trees!”’

St Barbe’s main ally, Chief Josiah Njonjo, called the clans together for a celebration along these lines, which it is said over 15,000 Kikuyu people attended. Fifty hand-picked warriors were given select status as Watu Wa Miti (Men of the Trees) and St Barbe devised a special handshake, a badge and later a secret password – Twahamwe (let’s work together) – to distinguish them from imitators who might steal their badges to gain access to the handouts of crop seeds and tree seedlings (mainly pencil cedar, cape chestnut and native olive varieties) that St Barbe persuaded the colonial administration to supply.

His memoirs say he had the Boy Scout movement in mind as a model. But he must have been aware of the powerful influence of oath-swearing as a feature of male initiation rites and clan identity among the Kikuyu: the banning of secret oaths would lead, 30 years on, to Independence by way of the Mau-Mau revolt.

At this point it all seemed innocent enough, however, and certainly it had a positive effect on the living conditions of many Kikuyu people, who reclaimed large holdings of land, while the Forest Service in due course derived a handy share of sustainably harvested timber from the scheme. But St Barbe fell out with his superiors in Kenya and was transferred to West Africa to serve as Assistant Conservator of Forests in Nigeria.

Here he managed forests of African mahogany (Khaya) on a sustained yield basis, trying to apply the relatively new principles of silviculture he had learned at Cambridge. He found himself ‘issuing permits to fell tens of thousands of pounds worth of mahogany with a mere pittance of £100 a year to spend on reafforestation’.

St Barbe was winning his battle for a more measured approach to running Nigeria’s forests when recurrent malaria forced him to return home. No sooner had he risen from his sickbed than the Colonial Office posted him off to what was then the British Protectorate of Palestine, where he somehow managed to rope leading Muslim, Christian and Jewish clerics into a scheme to replant six amenity and fruit tree species common in biblical times, on eroded slopes and exposed roadsides throughout the territory. Influential friends in England raised enough money to fund 42 nurseries.

Saving the redwoods

In 1929 St Barbe was offered a free passage by an ocean cruise line director on one of the line’s empty boats heading west to ply winter trips from New York to Bermuda. He decided on the spur of the moment to quit his civil service post and use this gift, he wrote, ‘to set out on a tour of the world’s forests with little more than a fiver and a free ticket to New York, only this time with my Palestinian films and slides illustrating The Life of a Forester in Kenya and in the Mahogany Forests of Nigeria. It was a serious blow to me when the customs officer charged duty on my film, leaving me with five dollars.’

A providential encounter with the publisher Lincoln McVeigh at a gentlemen’s club gave rise to his first book. He dictated, edited and delivered Men Of The Trees inside 20 days, then set off on his lecture tour with advance fees adding up to $1,000 in his pocket. The trip led him to California and to his first encounter with the mighty giant redwoods and sequoias of north-western America’s temperate rainforest.

It was the start of a love affair that would last until the very end of St Barbe’s life. For him, ‘these magnificent and fantastic trees’ were, as he exclaims in Dance of the Trees, ‘the biggest and most beautiful trees in the world. They have been standing for thousands of years. They tower hundreds of feet into the air and around their feet bloom giant irises, themselves standing nine or ten feet high.’

There was already a Save the Redwoods League campaigning inside America to save individual trees or small groves. St Barbe decided that the top priority was to preserve substantial areas of forest to ensure the survival of the whole environment. His world tour took him further westwards and across the Pacific to New Zealand and Australia, where he founded Men of the Trees chapters that still flourish.

When he returned to London the first thing he did was to call a meeting at the headquarters of the Royal Geographical Society to set up a Save The Redwoods Fund to buy up land holdings and lumber concessions in and around Mill Creek, an area St Barbe described as ‘the heaviest stand of timber in the world’. St Barbe returned to the USA every year for eight years to campaign and raise funds for Save The Redwoods initiatives. By 1945 the area of conserved redwood forest stood at 17,000 acres. It had expanded to over 100,000 by 1960, most of it within protected areas managed by the state authorities.

St Barbe also campaigned on issues surrounding Douglas fir and boreal forests in Canada and giant eucalypts in Australia. He doorstepped Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 with a plan to create a Civilian Conservation Corps of 500,000 unemployed men to ‘serve the land, assist agriculture and stem the oncoming timber famine’ by planting trees to prevent dustbowls. President Roosevelt acted on this idea and six million young men worked in 2,600 CCC camps in the nine years the corps lasted.

After the second war

After World War II, St Barbe worked in Germany on restoring the landscape and in South Asia on steps to contain the Thar Desert. He became increasingly preoccupied with his Green Front scheme for reforesting the Sahara and he led two expeditions across the desert to seek evidence of prehistoric or pre-agricultural forests. He also sought UN backing for a World Charter for Forestry and was one of the first public figures to comment on rainforest destruction in the Amazon Basin.

His last foreign tour, at the age of 92, was in the USA and Canada. He witnessed the dedication of Redwood National Park as a World Heritage Site. Then he revisited Saskatchewan University, the scene of his first overseas venture. There he planted a tree to commemorate World Environment Day, and died two days later. A hard-bitten pressman, Sam Blackwell of the Southeast Missourian, saw St Barbe during the Redwood National Park dedication:

He was very old and frail. The young environmentalists taking care of him treated him with respect and awe. They said I could speak with him as soon as he awoke. When he did wake up he could barely speak, and the words he said were difficult to understand. It didn’t matter. He had a presence that made you happy to be in his company. We went outside to take his photograph. Spontaneously, he did what people who scorn environmentalists make jokes about: he hugged a tree. I don’t mean he put his arms around it. He hugged it like I hug my old friend Carolyn, like he never wanted to let it go. I began to understand. We do need to care, of course, for everything and everyone.

The legacy

So much for the legend. But what of the legacy? In the UK the Men of the Trees, mostly for reasons of political correctness, became the International Tree Foundation in 1992. There are now 22 branches across the country involved in practical tree planting and conservation work in Britain, and both branches and headquarters fund tree planting projects in Africa and India.

In Australia too, where there is a Men of the Trees branch in every state, each with a highly active, predominantly youthful membership, there is no disputing the staying power of St Barbe’s ideas and example.

In North America, however, his memory is far from evergreen. Most of the leading US organisations that were historically involved in redwood conservation, including the Sierra Club and the Save The Redwoods League, make no mention at all of him in their literature or in their online archives.

Similarly, definitive histories published in America in recent decades about the battle to conserve the redwoods make no mention of St Barbe. His was – it seems – more of a walk-on part than the starring role awarded to him in his own books and in eulogies by dedicated supporters. It is safest to say that he raised some handy funds and raised the stakes by voicing British concern over the redwoods’ plight, flagging the international significance of the issue.

In Africa, where you could say it all began, the situation is more complex. St Barbe’s ideas about Africa’s ecological and social history range from perceptive firsthand observations through to extremely sketchy – sometimes downright barmy – ideas and theories. He claimed in Africa Drums (1945) that he had been ceremonially initiated as a blood brother into a secret council of elders, the Kiama, that, he said, exerted hidden influence all over Africa, dating back to a Golden Age when 'men of the forest' ran the continent. This claim, though nonsensical, was backed up in his preface by a University of London Professor of Anthropology, Malinowsky, who should have known better.

St Barbe also believed in the ‘drought follows the plough’ hypothesis that human overcrowding, intensive cultivation and overgrazing leads to deforestation, which in turn leads inevitably to desertification, soil loss and famine. He was not alone in this belief. It was received wisdom among professionals and academics for many years.

Recent generations of researchers have begun carefully to untangle this narrative and to show that it does not stand up to close examination. More people can just as easily lead to more trees as to fewer trees. Evidence of ancient forests in places now covered by desert are more likely to be evidence of natural processes of climate change than of human destructiveness.

As Jeremy Swift points out in 'The Lie of the Land', a well-known collection of studies that explode myths surrounding deforestation in Africa: ‘The desertification story is a particularly interesting example of a narrative [explicable] in terms of the convergent interests of governments, aid agencies and scientists that has persisted in the face of rapidly mounting scientific evidence that it was inaccurate, and that the policies it suggested did not deal effectively with dryland degradation.’

Without straying too far into a scholarly quagmire, it is enough to say that St Barbe shared a widely held set of misconceptions about the situations he encountered in Africa that worked to the ultimate detriment of his programmes of action. Though these programmes were undeniably well-meant, little physical trace can now be found of them. The cedar and mahogany forests he planted and nurtured in Kenya and Nigeria have mostly been plundered, apart from a few embattled relics. Watu wa Miti did not survive decolonisation.

The Green Belt Movement

Yet maybe St Barbe’s African works were not entirely in vain. For his personal influence continued to affect at least one contemporary champion of Africa’s forests, the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai, founder of Kenya’s Green Belt Movement and by far the most respected voice for forest protection in modern Africa. ‘I met Richard St Barbe Baker on at least three occasions in the company of ex-Senior Chief Njonjo,’ she told me. ‘On one occasion they visited me at the office of the National Council of Women of Kenya and wanted to know more about my idea of planting trees with communities. They told me about the Men of the Trees and invited me to join, which I did.

‘The second time I met him and we talked about our work, especially his work in Australia and Canada. The third time was during the UN conference on New and Renewable Sources of Energy in 1981 here in Nairobi. He participated in planting trees along with other delegates on a farm near Naivasha, in the great Rift Valley. I still remember how he, Njonjo and I walked hand in hand away from the site after the tree planting ceremony.’

Wangari Maathai was unaware of the Men of the Trees when she started her Green Belt Movement and St Barbe’s organisation is no longer active in Kenya, but she sees the movement as ‘a continuation of what the two men started in the 1920s, adding: ‘During the short period I knew Barbe Baker I found him a warm and inspiring man full of energy, ideas and hope that the young generation would embrace the concerns of the older generation and would save the planet from environmental disaster. We may not have realised that vision but we continue to be inspired by their commitment.’

There can be no arguing with a testimonial like this. Wild and woolly though some of his ideas may have been, the major worth of St Barbe resided in his spirit and vigour. His life proved that it is not enough just to know trees or understand the science of coexisting with them. If we wish to deserve to protect them, we must also love them.

Sources

Melissa Leach and Robin Mearns (Eds) 1996. 'The Lie of the Land: Challenging received wisdom on the African Environment.' (The International African Institute in association with James Currey (Oxford) and Heinemann. 1996)

Richard St Barbe Baker 'My Life – My Trees' (P/B reprint. The Findhorn Press, 1970.)

Wangari Maathai, 'The Green Belt Movement: Sharing the approach and the experience'. (Lantern Books, New York.. 2004). See also the movement's own website here.

The International Tree Foundation, Sandy Lane, Crawley Down, Crawley, West Sussex RH10 4HS; 01342 712536;

Court Drawing: Laurie McGaw/Toronto Star

Court Drawing: Laurie McGaw/Toronto Star

Photo credit: Stefano Paltera / North American Solar Challenge

Photo credit: Stefano Paltera / North American Solar Challenge