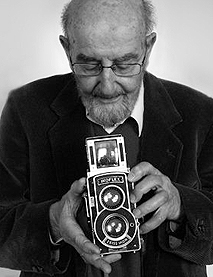

This remarkable photo is one of the most famous images taken by the distinguished photographer and cinematographer Wolf Suschitsky.

Back in 1979, he sent me a print of it as a gift with a very sweet note after I told him the story I am about to relate and it now sits centre stage above my gas fire in my work room, framed in black - a haunting image of my totem animal.

I was a kid back in the fifties when I saw Guy at London Zoo. For his whole life in captivity he was the zoo's main attraction, much-loved and famous from his numerous tv appearances. Like a giant hairy Buddha he sat there staring back at me, an extraordinary unearthly being.

The experience stuck.

The basics of Guy's story are well recorded. Born on 30th May 1946, he was captured in the French Cameroons and arrived at the zoo on Bonfire Night the following year (hence his name) as a tiny baby, weighing 231bs (10.4kg) and holding a small, tin hot-water bottle. A Western Lowland Gorilla with the delightful Latin name of Gorilla gorilla gorilla, he grew to a massive size. According to the archives of the Zoological Society of London, at his heaviest in 1966 he weighed 34 stone (215kg), stood 5ft 4in tall (1.1m, with knees bent) and had a 9ft (2.7m) arm span. His neck was 36in (0.9m) in circumference, bigger than an average man's waist.

He was introduced to Lome, a female gorilla, in the late '60s, but they never mated. His favourite foods were cucumbers, melon, pineapple and dates. He had a big fan club, members of which would send him cards on his birthday. The Heatons, from Leeds, regularly spent a week of their annual holiday with him. When small birds flew into his cage he would pick them up, gently examine them, and then set them free.

Freedom was something he never experienced himself, and his celebrity led to his death from a heart attack in 1978 while undergoing surgery. The operation was to deal with infected teeth, rotted from all the sweets fed to him by tourists. What an ignominious end for such a grand creature.

In a strange way, Guy's death changed my life and consciousness, coming hard on the heels of my discovery of Peter Singer's book ‘Animal Liberation’ and the Animal Liberation Front. At that time I was working as Dick Tracy, investigative journalist, for the NME, and was one of the first journalists to write about ALF activities. It is hard to grasp now how strange these ideas and actions seemed at the time.

Fired up with new feelings and emotions, it was a small step for me to produce a badge (through `Better Badges', main producer of punk badges at the time), a black and white beauty that had a picture of Guy on it, and the word 'Animal Liberation'. It was a hit.

While I continued to write animal pieces for the NME, I could see this was a much bigger story, and it was then I invented 'The Beast', which began life as two four-page supplements in International Times before becoming a magazine in its own right. The first issue, unsurprisingly, had Guy on the cover.

The magazine, which I produced with Michael Marten and designer Mikki Rain, ran for ten issues over two years (1979-1981) and was, in retrospect, a pioneering effort, coming as it did at a new phase in the growth of a movement for a change in our attitude towards animals that is now global in extent. Amazingly, the whole set of the original magazines have now been carefully digitised and can be read in total online.

Together with my colleagues Mike Marten and John Chesterman, I also produced two animal books in this period - a beautiful photo book entitled ‘Weird and Wonderful Wildlife’ and a modern-day bestiary called ‘A Book of Beasts’. Strangely, it happened that both books were published in the same week, and just as I was on the brink of setting out to do some publicity work on them, came the news that Guy the Gorilla was going to be put on exhibition -stuffed - in the Natural History Museum.

A chill went through me, and I knew I was going to have to do something. Which is why on a brisk autumn day in November 1982, I was standing outside the Museum with my dear departed friend John Chesterman, handing out protest leaflets that I had produced and written on the sad story of Guy, an item that also ran as a piece in Time Out.

Then I was ushered in to do a live interview for Radio 4 alongside someone from the museum who obviously had different views on the subject. We were positioned in front of Guy - a painful experience and, I felt, yet another ignominy.

Of course, times have changed. The idea of housing a huge gorilla in a tiny cage for all its natural life would now be unacceptable. The growth in our understanding of primates over the last 30 years has altered our relationship to them. We now know how genetically similar we are to apes, and how intelligent they are.

The current conservation status of Lowland Gorillas is 'critically endangered'. Estimates from the 1980s put the total population in seven Central African nations at fewer than 100,000. The number remaining is now believed to be less than half this, due to disease and hunting. Good news came in August 2008, when the Wildlife Conservation Society revealed the discovery of more than 125,000 and of these gorillas, previously untallied, but the species as a whole remains vulnerable to the Ebola virus, poaching and deforestation.

According to Wikipedia, there are 550 Western Lowland Gorillas in zoos worldwide, many captive breeding programmes underway. In fact there's even an online stud book.

The spirit of Guy still haunts me. He stares at me from the photo, the shadow of the bars on his face, a constant reminder of the plight of animals in our modern world; also of fugitive personal memories and past emotions. Those were important times.

*

By a set of fortuitous circumstances, when writing this piece, the opportunity arose for a phone interview with Wolf Suschitsky, now a remarkable 100 years old. [Now 103] |

| Source: United Nations of Photography |

Principally a cinematographer of some 25 feature films, of which the best-known is ‘Get Carter’, he always carried a still camera and his photos have been exhibited internationally. On the phone he sounded bright and sprightly. He has a sharp memory and a voice that still retains a distinctive Austrian accent.

He was happy to recall his memories of that day in 1958 when, then aged 46, he took his iconic shot of Guy. He told me that at that time he was working as an assistant to director Paul Burnford, who was making a series of zoo films. Wolf took advantage of this to start shooting portraits of the animals, which zoologist Julian Huxley (brother of Aldous) liked very much. They later together made a book about mammals entitled ‘The Kingdom of the Beast’. According to Suschitsky, Huxley said Guy "was the most magnificent animal he'd ever met."

"I was helped by Mr Smith, head keeper of the Old Monkey House, as it was called. I put the lens of my Hasselblad through the bars and the keeper was there with a big iron bar to keep Guy away, in case he went for me, because he could reach out about three feet.

"Guy was sitting at the back of a terribly small cage and the shadows of the bars were on him. After a while I had to reload my camera, and the keeper said, `I'll just go and get him some more grapes to keep him in place where he is' and he put that bar, which had a hook at the end, onto the cage.

"While he was away, Guy came slowly forward, picked up the iron bar and took it into the cage and put it in front of himself. And when the keeper came back, he immediately said: 'Give me that bar'. No reaction at all. 'Give me that bar'. No reaction. Third time, Guy picked up a sweet wrapper and brought it to the keeper. He was very intelligent, of course, and knew exactly what was wanted, and eventually he gave it back."

In an interview with The Guardian about this picture, Wolf Suschitsky described Guy as a "marvellous ape living in a tiny cage... I don't think he was happy - I don't see how he could have been".

"I was helped by Mr Smith, head keeper of the Old Monkey House, as it was called. I put the lens of my Hasselblad through the bars and the keeper was there with a big iron bar to keep Guy away, in case he went for me, because he could reach out about three feet.

"Guy was sitting at the back of a terribly small cage and the shadows of the bars were on him. After a while I had to reload my camera, and the keeper said, `I'll just go and get him some more grapes to keep him in place where he is' and he put that bar, which had a hook at the end, onto the cage.

"While he was away, Guy came slowly forward, picked up the iron bar and took it into the cage and put it in front of himself. And when the keeper came back, he immediately said: 'Give me that bar'. No reaction at all. 'Give me that bar'. No reaction. Third time, Guy picked up a sweet wrapper and brought it to the keeper. He was very intelligent, of course, and knew exactly what was wanted, and eventually he gave it back."

In an interview with The Guardian about this picture, Wolf Suschitsky described Guy as a "marvellous ape living in a tiny cage... I don't think he was happy - I don't see how he could have been".

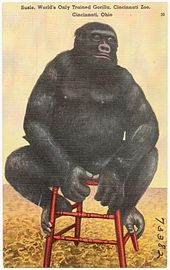

FOOTNOTE on CINCINNATI ZOO

In 1931, Robert J. Sullivan permanently loaned the zoo a female gorilla named Susie. Captured in the Belgian Congo, Susie was first sold to a group of French explorers who sent her to France. In August 1929, Susie was transported from Europe to the United States aboard the Graf Zeppelin accompanied by William Dressman.

In 1931, Robert J. Sullivan permanently loaned the zoo a female gorilla named Susie. Captured in the Belgian Congo, Susie was first sold to a group of French explorers who sent her to France. In August 1929, Susie was transported from Europe to the United States aboard the Graf Zeppelin accompanied by William Dressman.

After Susie completed a tour through the United States and Canada with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, Sullivan purchased Susie for $4500.00 and loaned her to the zoo. Dressman, who stayed on as Susie’s trainer after she was loaned to the zoo, taught her how eat with a knife and fork and orchestrated two performances every day. Susie was so popular that on her birthday on August 7, 1936, more than 16,000 visitors flocked to the zoo. Susie remained one of the most popular animals at the zoo until her death on October 29, 1947. Her body was donated to the University of Cincinnati, where her skeleton remained on display until it was destroyed in a fire in 1974.

Gorilla Shooting Sparks Memory of Infamous Brookfield Zoo Incident

Many Chicagoans remember that on Aug. 16, 1996, a small boy climbed a railing and fell 18 feet into the gorilla den at the Brookfield Zoo. An 8-year-old female gorilla named Binti Jua made national headlines when she picked up the unconscious boy and protected him from the other primates. The act of kindness came as a surprise to many of the guests who said they feared Binti Jua would maul the 3-year-old. The boy, whose identity was never released, made a full recovery, and Binti Jua's heroic deed caught on camera gained her national attention. Binti was named Newsweek's Hero of the Year and one of People magazine's most intriguing people of 1996.

Gorilla Shooting Sparks Memory of Infamous Brookfield Zoo Incident

Many Chicagoans remember that on Aug. 16, 1996, a small boy climbed a railing and fell 18 feet into the gorilla den at the Brookfield Zoo. An 8-year-old female gorilla named Binti Jua made national headlines when she picked up the unconscious boy and protected him from the other primates. The act of kindness came as a surprise to many of the guests who said they feared Binti Jua would maul the 3-year-old. The boy, whose identity was never released, made a full recovery, and Binti Jua's heroic deed caught on camera gained her national attention. Binti was named Newsweek's Hero of the Year and one of People magazine's most intriguing people of 1996.