Here we see Peter printing two pages of the pamphlet that Paine wrote when he was in Lewes, arguing the case for a wage rise for the Excise Men. Peter is shown here inking the metal type.

Here he is attaching a dampened piece of paper which is then brought over to make contact with the type.

Similar procedure for the second page.

Here is the finished page, fresh off the press.

Peter is printing a larger size for demonstration purposes. Here he shows the original size that such a pamphlet would be.

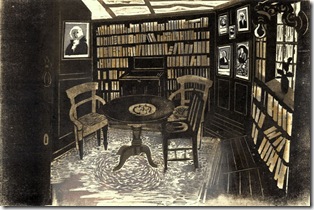

Below is one of her own beautiful prints from the book which shows the ante-room off Westgate Chapel, next door to Bull House where Tom Paine lived. Carolyn says: "Paine would have probably used the chapel - in fact he and Elizabeth Ollive took their wedding vows there before going through the legal ceremony in St Michaels church over the road. I think this little room is one of the nicest in Lewes, still smelling of the dust of the eighteenth century.'

As chance would have it, I came across a 1989 review by Richard Bernstein in the New York Times of 'Revolution in Print: The Press in France 1775-1800', edited by Robert Darnton and Daniel Roche., which read in part:

'Mr. Darnton and Mr. Roche open the curtain with chapters on the world of publishing and censorship in the last years of the ancien regime, showing how the system of control, built on a proto-totalitarian thought police, was already teetering on the brink of collapse. In the 1750's, 40 percent of those sentenced to the Bastille (136 of 339 prisoners) were connected with the book trade. Smugglers of illicit publications often concluded their lives as galley slaves. And yet censorship failed to strangle the circulation of what the entire publishing industry called ''philosophical'' books, a code word for all materials, whether political or pornographic, that were banned by the thought police. These ''philosophical'' works were printed in Switzerland and brought into France by a host of clandestine methods. A market existed for both ideas and illicit entertainment, and risk-taking entrepreneurs found ways to satisfy it.'

This bears interesting comparison with the current situation in Iran. See recent story by Brian Stelter in the New York Times See also Previous Post: IRAN: TECHNOLOGICAL DEJA VU

No comments:

Post a Comment