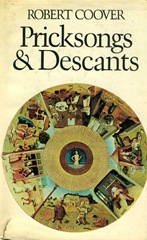

Top: First edition of ‘Pricksongs & Descants’ [Jonathan Cape. 1971] Cover: Detail from The Seven Deadly Sins’ by Hieronymous Bosch. Author photo: Tony Keeler.Below: First edition of ‘Gerald’s Party’ [ Heinemann. 1986]. Cover: Barbara Nessim. Inscribed to me: ‘For John May, Heavy drinker. welcome guest.’

This post and the one following are about two writers I interviewed way back when, who have swum back into my consciousness through discovering and reading copies of their more recent work and then returning back to the original books which turned me on to their work in the first place. If that makes sense.

I remember exactly where I was when this copy of ‘Pricksongs & Descants’ came into my possession. It was in the box office of a huge venue in Seven Sisters Road in London where the underground press were staging regular gigs with bands like the Pink Fairies and Hawkwind. I had been put on the door because I didn’t know anybody and thus was less likely to let anyone in for free. Joy Farren gave it to me – my first ever review copy – for me to write about it for International Times’. I was 21. A collection of short fictional pieces. I thought is was magical. On the dusk jacket are two Coover quotes about his writing:

‘And it is above all the need for new modes of perception and fictional forms able to encompass them that I, barber’s basin on my head, address these stories.’

‘The novelist uses familiar mystic or historical forms and to conduct the reader to the real, away from mystification to clarification, away from magic to maturity, away from mystery to revelation.’

In Feb 2009, the New Yorker published a long piece by Louis Menand entitled ‘Saved From Drowning’ about ‘Hiding Man’, Tracy Daugherty’s biography of the writer Donald Barthelme. It begins:

‘n the spring of 1983, Donald Barthelme invited about twenty people to dinner at a restaurant in SoHo. The guest list included Thomas Pynchon, John Barth, William Gaddis, Robert Coover, John Hawkes, William Gass, Kurt Vonnegut, Walter Abish, and Susan Sontag. All of them turned up except Pynchon, who was out of the state and sent his regrets, and the writers made short speeches about their work and toasted their friendship. The affair became known as the Postmodernists Dinner.

‘As with many occasions organized to celebrate accomplishment, the mood was valedictory. In the nineteen-sixties, most of those writers had been turning the world of American fiction on its head; in the nineteen-eighties, they were the subjects of doctoral dissertations. They had become aldermen of the towns they once set out to burn down. They had also fallen out of step. The action in American fiction after 1975 no longer involved experimental-ism and mixed media; it involved minimalism and a kind of straightforward realism that many of the people in the room probably thought they had left for dead long before. ‘

One year after this dinner, Robert Coover’s book ‘Gerald’s Party’ was published in the UK - his first major novel since the 1970s - and I was fortunate indeed to have a chance to interview him – on April 28th 1986, at his agents house in Ladbroke Grove. The next day I was 36. As often happens, the interview was never published but I still have the cassette tape – now of some historical value. ‘The Observer’ review of the book echoed Menand’s comments above:

‘Robert Coover’s new novel displays all the manic energy, the black and bizarre humour that made his name back in the Sixties. But his determinedly outrageous bad taste now seems rather strident, even a little dated.’

In 2009, there was a wonderful feature in The Guardian Review by Harif Kunzru entitled ‘Robert Coover: A Life in Writing’ [read it in full here] which rightly celebrates Coover’s achievements.

‘Coover, along with such writers as Thomas Pynchon, William Gass, Donald Barthelme and John Barth, broke open the carapace of postwar American realism to reveal a fantastical funhouse of narrative possibilities. His relentless experimentalism, combined with a sly and often bawdy humour, have made him a writer's writer, a hero to those who feel smothered by the marshmallowy welter of pseudo-literary romance that dominates contemporary fiction. Refreshingly unconcerned with psychology, sympathy, redemption, epiphanies and conventional narrative construction (or rather, concerned with undoing these things), he is relatively unknown in Britain, where three of his books (Pricksongs & Descants, Gerald's Party and Briar Rose & Spanking the Maid) have recently been released as Penguin Modern Classics.’

Robert Coover is now 80 and is on Facebook. I have sent him a copy of this post. You can read more about him here:

Wonderful readings by Coover (including ‘Noir’ and ‘The New Thing’

Interview by Jonathan Derbyshire in the New Statesmen (2011)

You helped found the Electronic Literature Organisation. When did you first become interested in the literary possibilities opened up by digital technology?

In the late 1980s. It just seemed obvious to me that the world was going to go digital. Everything about it made it seem inevitable, and if that was true then I thought my [creative writing] students should be aware of it and know how to live inside this new world.

Is "electronic literature" a threat to books?

It won't displace books, though I don't think it's good for books. I think it's good for literary art of another kind. And the literature produced may be far more compelling and popular than print culture currently is.

No comments:

Post a Comment